This webpage presents findings from 1 September 2024 to 31 August 2025. Comparisons with 2023-24 use the same date range.

Introduction

The Fundraising Regulator works to protect the public from poor fundraising practices. We do this by helping organisations follow the standards set out in the Code of Fundraising Practice (‘the code’) and by investigating complaints that cannot be resolved by organisations themselves. We also act proactively where fundraising has caused, or has the potential to cause, harm.

This report summarises key insights from our casework during 2024–25. All cases assessed during this period were considered under the 2019 edition of the code, which has since been updated.

Number of cases

A case refers to any issue recorded with us, including complaints or self-reports.

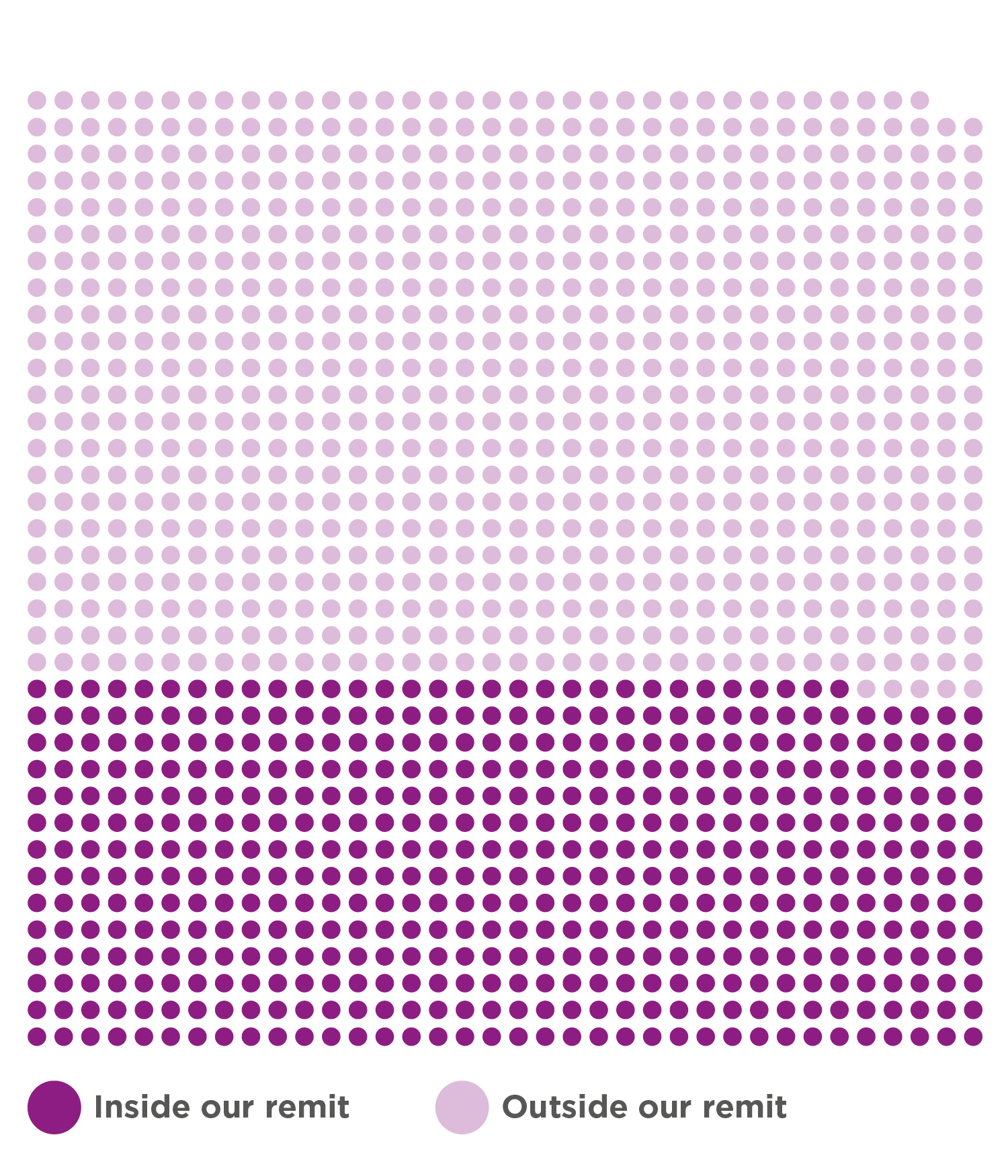

During the reporting period, we received 1,284 cases, a 9% increase on the previous year. We closed 1,294 cases in total, including cases opened in earlier reporting periods.

Of the cases closed:

- 499 (39%) related to charitable fundraising and fell within our regulatory remit.

- 795 (61%) were outside our remit. These primarily concerned personal cause fundraising appeals, suspected fraud, or wider governance issues that were more appropriately handled by other regulators or organisations.

Self-reporting

Self-reporting is when a fundraising organisation proactively tells us that it has identified, or suspects it may have identified, a breach (or potential breach) of the code in its charitable fundraising activities.

During the reporting period, we received 19 self-reports, compared with 31 in 2023–24. None of these self-reports resulted in a formal investigation:

- In most cases, the organisations involved had already taken the reasonable steps we would expect to address the issues reported.

- In a small number of cases, we provided additional advice to help improve compliance with the code and reduce the risk of similar incidents occurring again.

- In two cases, we opened compliance casework to seek further information and work with the organisations to ensure compliance with the code.

Seven of the self-reports related to face-to-face fundraising and covered four separate incidents. In three of these incidents, both the charity and its contracted fundraising agency submitted self-reports.

Types of complaints

A complaint is a distinct type of case, typically raised by the public or through external intelligence. Only in-remit complaints are counted within our analysis below.

Overview

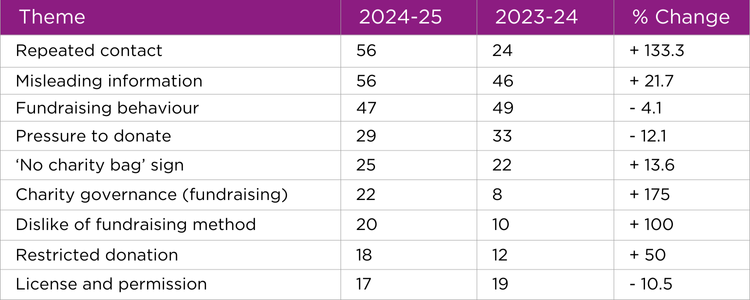

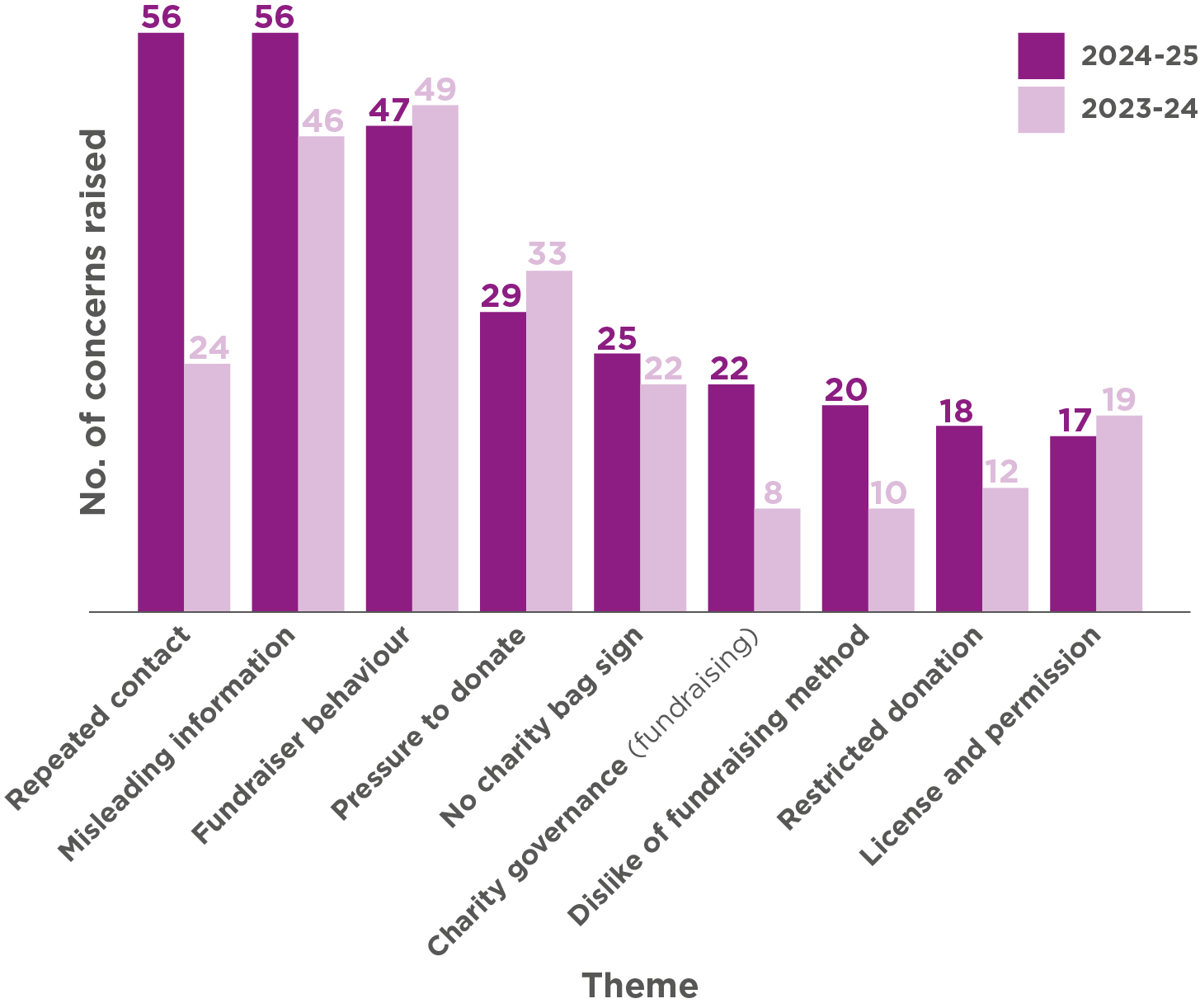

The table below shows the most common complaint themes and how they compare with the previous year.

Fundraising methods

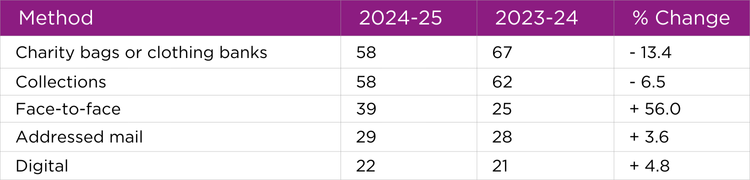

The most complained-about fundraising methods during the reporting period were charity bags or clothing banks and collections, followed by face-to-face, addressed mail and digital fundraising.

Insights from investigations

If we have information that indicates a serious breach of the code, and/or where an organisation will not engage or co-operate with us about compliance with the code, we may open an investigation.

This section sets out the key themes and emerging issues identified through our investigations over the past year. It highlights the trends we are seeing across cases and provides learning to help organisations strengthen their fundraising practices and meet the standards in the code.

People in vulnerable circumstances

We undertook several investigations into how charities and fundraising agencies engage with people in vulnerable circumstances. These identified multiple breaches of the code, particularly where organisations failed to recognise or appropriately respond to a donor’s vulnerability.

Fundraising from a defined group of individuals

We have seen a growing number of situations where organisations ask a defined group of individuals, such as members of a faith-based community or alumni networks, to donate. The funds raised were used by the organisations for charitable purposes.

In some instances, organisations did not recognise that these activities are charitable fundraising and that they must follow the code. This is an area where we are seeing increased misunderstanding and inconsistent practice.

Fundraising by some Community Interest Companies (CICs)

CICs are businesses established to benefit the community but are not registered charities and are not subject to the same robust regulations that apply to charities.

Last year we reported a significant rise in complaints about the fundraising practices of a small number of CICs. This trend has continued into 2024–25.

Eighteen per cent of all complaints we received related to CIC fundraising, up from 12% in 2023–24. Many of the concerns involved CICs previously identified, as well as new CICs conducting similar activities.

Transparency data

Any complainant and/or the organisations involved in the complaint may request an independent external review of our investigation decisions, or our decisions not to investigate.

External review of our decisions

In 2024–25, we received three requests for an external review of our decisions: two relating to investigation decisions and one concerning a decision not to investigate.

- For one investigation decision, the reviewer found grounds to review the case. Although they agreed that no changes were needed to our findings – and the charity accepted this – they recommended improvements to the wording of the decision and the published summary.

- For the non-investigation decision, the reviewer found no grounds to reopen the case.

- For the third request, which related to another investigation decision, the reviewer found that the criteria for external review were not met.